- Key Insights

- Regional Analysis of Alcohol Use Throughout Provinces in Canada

- Alcohol Use Trends in Halifax and Canada

- Trends in Alcohol-Related Risks by Demographic

- Costs and Consequences of Heavy Alcohol Use

- Interventions and Solutions to Alcohol-Related Problems in Halifax

- The Future of Alcoholism in Halifax

- References

Key Insights

| The Canadian Public Health Association shows that in 2019, 18.3% of Canadians reported experiencing heavy drinking. Based on data from the 2017 Canadian Health Info Base, Nova Scotia ranked fairly low in terms of its percentage of the population who engaged in drinking alcohol in the past 12 months, at 73.80%. According to the Halifax Regional Council’s records, the city experienced a regular increase in alcohol-related emergency department intakes between 2015 and 2020, with numbers growing from 1,071 to 1,202 cases. Statistics Canada reveals that in 2023, more men than women were in the high-risk category for drinking, at 19.3% of the population. The same report also shows that people aged 55 to 64 had the biggest portion of people in the high-risk category for drinking, at 17.4%. |

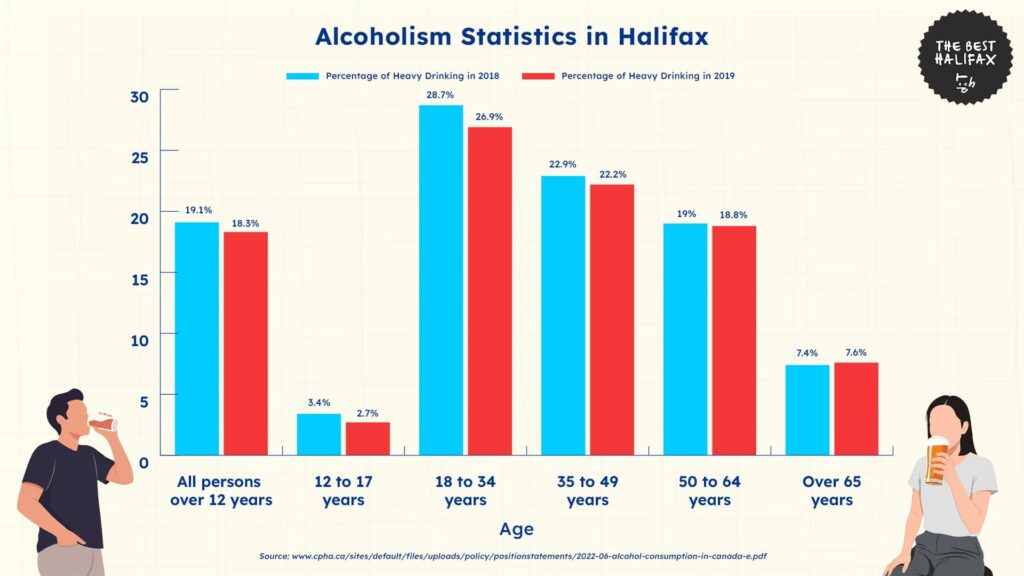

Data from the Canadian Public Health Association reveals alarming insights into alcohol consumption trends across the country.

In 2018, 19.1% of Canadians aged 12 years and older reported heavy drinking, which is defined as consuming more than 60g of pure alcohol on a single occasion at least once per month.

By 2019, this figure declined slightly to 18.3%, but age-specific data show that certain groups remain consistently at higher risk.

The highest rates were reported among those aged 18 to 34 years, with 28.7% in 2018 and 26.9% in 2019.

Notably, this age group consistently had higher rates than all others, suggesting that young adults are the most likely to engage in heavy drinking behavior.

Meanwhile, the 35 to 49 age group follows, with 22.9% reporting heavy drinking in 2018 and 22.2% in 2019, which shows that risky drinking behavior remains common into mid-life.

Conversely, the 50 to 64 age group had slightly lower rates, at 19.0% in 2018 and 18.8% in 2019.

Older adults aged 65 years and older consistently showed the lowest levels of heavy drinking. In 2018, 7.4% of this group reported heavy alcohol use, though this number increased slightly to 7.6% in 2019.

Youth aged 12 to 17 years had the lowest reported rates overall. In 2018, 3.4% of this group engaged in heavy drinking, before dropping to 2.7% in 2019.

Altogether, the data illustrate a curve in heavy drinking that peaks in early adulthood and slows down with age.

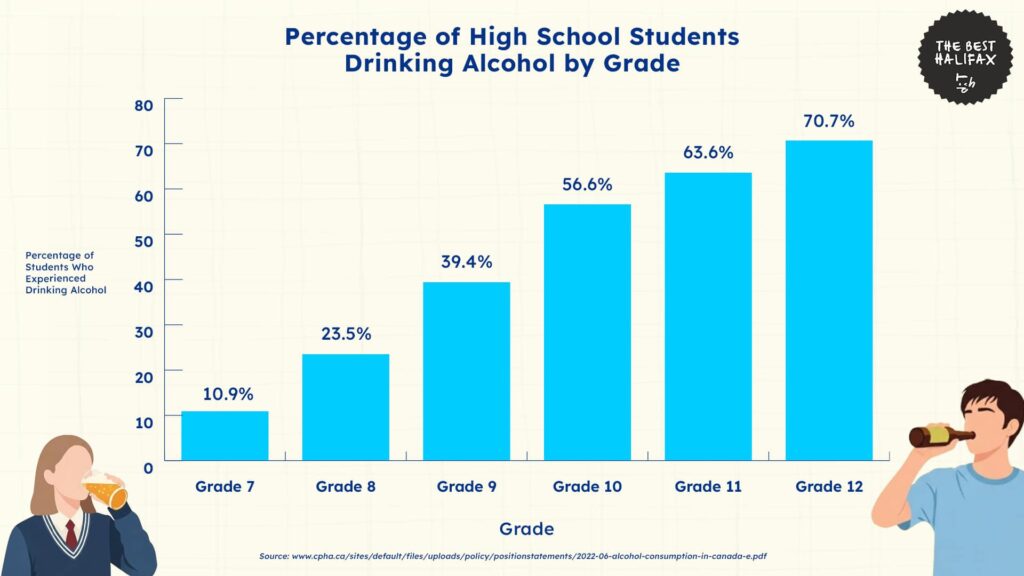

The data also shows the percentage of high school students who engage in regular alcohol consumption, broken down by grade.

Alcohol use among Canadian students increases steadily and sharply from Grade 7 through Grade 12, showing a clear pattern of early exposure to alcohol use.

In Grade 7, only 10.9% of students reported having consumed alcohol. This relatively low figure reflects limited access and possibly stronger parental and institutional controls during early adolescence.

However, by Grade 8, the number more than doubled to 23.5%, suggesting that exposure and curiosity begin to increase rapidly after the first year of secondary school.

The percentage rises again to 39.4% in Grade 9, which is a year when students are increasingly influenced by older peers and may begin attending more unsupervised social settings.

In Grade 10, the majority of students, 56.6%, report having consumed alcohol. This indicates that by the age of 15 or 16, more than half of the students have tried alcohol.

By Grade 11, the rate increases further to 63.6%, and in Grade 12, it peaks at 70.7%.

This shows that by the end of high school, nearly three out of four students have consumed alcohol.

Regional Analysis of Alcohol Use Throughout Provinces in Canada

According to the 2017 Canadian Health Info Base, 78.2% of Canadians aged 15 years and older reported consuming alcohol within the past 12 months.

While this national figure reflects a high level of alcohol use across the country, an analysis of the rates for each province reveals significant differences.

The province with the highest rate of past-year alcohol use was Quebec, where 84.2% of residents aged 15 and older reported drinking in the previous year.

This was the only province to exceed the 80% threshold and was 6.0 percentage points higher than the national average of 78.20%. Quebec’s rate suggests that alcohol use is more common in everyday life compared to other parts of Canada.

Alberta followed with a rate of 78.8%, ranking second overall and slightly above the national average by 0.6 percentage points.

British Columbia and Saskatchewan were next, with 78.5% and 78.4%, respectively. These three provinces were closely aligned with national trends, suggesting moderate-to-high levels of alcohol use.

In Newfoundland and Labrador, 77.4% of the population reported drinking in the past year. This is 0.8 percentage points below the national average.

Ontario recorded a lower rate of 75.6%, which is 2.6 percentage points below the national average. Despite this, Ontario remains among the provinces with relatively high levels of alcohol consumption.

New Brunswick and Nova Scotia reported rates of 74.9% and 73.8%, respectively. These provinces are in the lower-middle range nationally, each reporting levels between 3.3% and 4.4% below the national average.

At the lower end of the scale, Manitoba reported a past-year alcohol use rate of 71.0%, which is 7.2 percentage points below the Canadian average.

Prince Edward Island had the lowest reported rate in the country, with 68.4% of residents consuming alcohol in the past 12 months.

This is 9.8 percentage points lower than the national figure and 15.8 percentage points lower than Quebec’s rate.

Provinces with lower alcohol use may reflect more conservative drinking norms or successful harm reduction programs, while those with higher rates may face increased challenges related to alcohol-related health risks.

Alcohol Use Trends in Halifax and Canada

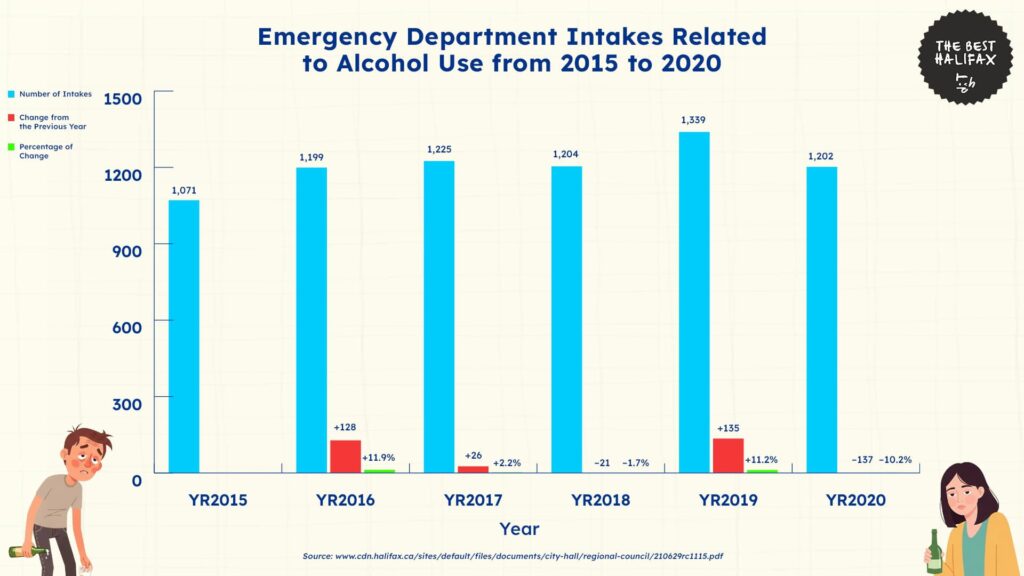

Trends in Alcohol-Related Emergency Department Intakes

According to the Halifax Regional Council’s records, between 2015 and 2020, there was a general increase in the number of alcohol-related emergency department intakes in Halifax.

In 2015, there were 1,071 cases. The following year, this number rose to 1,199, which is an increase of 128 cases or about 12%.

By 2017, the number increased again, reaching 1,225. While this was only 26 more cases than in 2016, this shows that there was still a continued increase in intake cases.

Notably, in 2018, there was a slight drop to 1,204, or a decrease of 21 cases. Despite this decrease, the overall rate for intakes still remained quite high.

The biggest rise came in 2019, when 1,339 people were admitted, which is also the highest number of intakes between 2015 and 2020. Moreover, this shows an 11.2% increase compared to 2018, and a 25% increase compared to 2015.

By 2020, this rising trend had changed substantially. That year, the number of intakes dropped to 1,202, which is a sharp decrease of 137 cases, or 10.2% less than the year before.

It is important to note that this drop coincides with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, when many public places were closed and fewer people were gathering outside.

This likely explains the decline in public intoxication incidents that led to fewer arrests and fewer admissions to the facility.

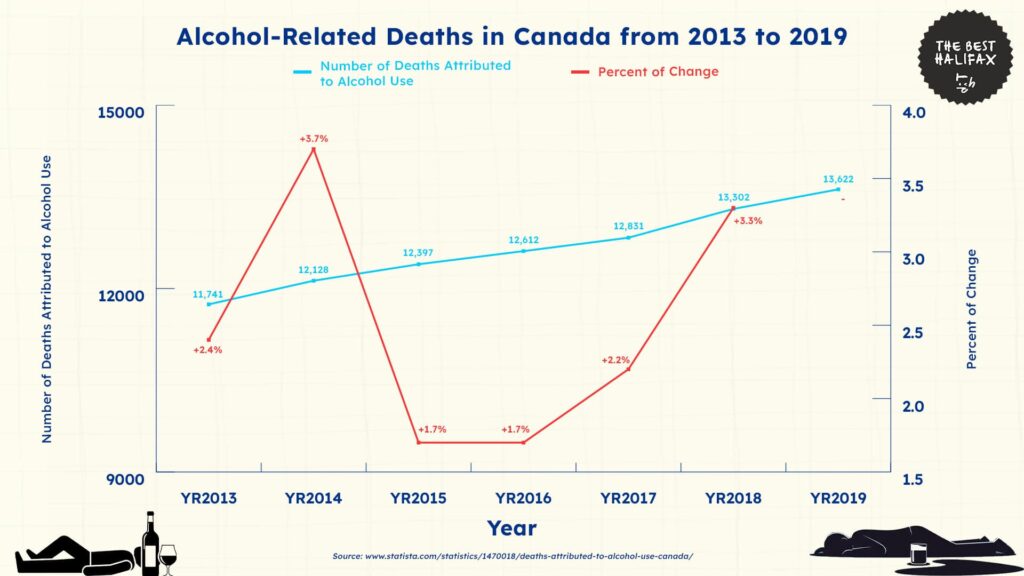

Trends in Alcohol-Related Deaths in Canada

Statistics Canada shows that between 2013 and 2019, the annual number of deaths attributed to alcohol use in the country has continued to increase.

In 2013, Canada recorded 11,741 deaths attributed to alcohol use. The total number of deaths then rose to 12,128 in 2014, which is an increase of 3.3%.

This early rise suggested that more Canadians were experiencing the long-term health consequences of heavy or sustained alcohol use.

By 2015, the number had reached 12,397, reflecting a 2.2% increase from the year before. Although the growth rate slowed slightly, it still points to an ongoing rise in alcohol-attributed deaths

In 2016, the trend also continued. That year, 12,612 deaths were linked to alcohol, which is a 1.7% increase over the previous total.

The following year, in 2017, the total climbed again to 12,831 deaths, which was another rise of 1.7%.

A more significant jump was recorded in 2018, when alcohol-related deaths rose to 13,302. This represented a 3.7% increase, which is also the largest gain during this period.

In 2019, the number reached its highest point in the period at 13,622 deaths, showing a further 2.4% increase compared to 2018.

When looking at the rise from 2013 to 2019, this means that there was a total increase of more than 1,800 deaths, or an overall growth of 16% in alcohol-attributed mortality nationwide.

Overall, these figures not only show a consistent rise in deaths linked to alcohol use but also point to a deepening public health challenge.

Trends in Alcohol-Related Risks by Demographic

Statistics Canada reveals how various demographics experience different risk levels when it comes to alcohol consumption.

Trends by Gender

According to the data, alcohol use patterns differ significantly between men and women in Canada.

In 2023, 58.8% of women reported consuming zero standard alcoholic drinks per week. This placed them in the no-risk category, meaning they had little to no exposure to alcohol-related health risks.

In comparison, only 49.9% of men reported no weekly alcohol consumption. This shows that a greater share of women avoided alcohol use entirely.

At the low-risk level, defined as drinking one to two standard drinks per week, 15.5% of women fell into this group.

Among men, the share was slightly lower at 14.9%. Although both genders were nearly equal in this category, it was the only risk group where women had a higher percentage than men.

Moderate-risk drinking, defined as the consumption of three to six drinks per week, was reported by 15.9% of men.

For women, the share was slightly lower at 14.6%. While the gap is smaller than in the high-risk group, it still reflects a pattern in which men are more likely to exceed safer drinking guidelines.

In the high-risk group, men held a significantly higher percentage, at 19.3% of the total, while women held only 11.1%.

When comparing all four levels, the data shows that women are more likely to either abstain from alcohol or consume very little.

Meanwhile, men are more likely to fall into higher-risk drinking categories. These differences point to gender-based patterns in alcohol use and suggest that men may face a higher burden of alcohol-related harm overall.

Trends by Age

Risk levels from alcohol consumption also varied across different age groups.

The youngest group, composed of individuals aged 18 to 22 years, had the highest proportion of people in the no-risk category.

A total of 67.1% of people in this group reported consuming no standard drinks per week. This suggests that most young adults either avoid alcohol entirely or drink very infrequently.

In the age group 23 to 34 years, 55.3% reported no alcohol consumption in an average week. This figure dropped to 51.9% for individuals aged 35 to 44 years and 50.7% for both the 45 to 54 and 55 to 64 age groups.

Among people aged 65 years and older, 56.9% reported no weekly alcohol use. These numbers show that alcohol abstinence or risk-free drinking is most common among young adults and seniors, while middle-aged adults are more likely to drink regularly.

Low-risk alcohol use was fairly consistent among most age groups. The 18 to 22 age group had the lowest percentage in this category at 11.4%, while all other groups reported between 14.6 and 15.6%.

This indicates that low levels of drinking are common across most age groups except among the youngest adults.

The rate of moderate risk drinking was highest in the 35 to 44 age group, where 16.6% consumed three to six drinks per week.

The 55 to 64 group followed at 16.3%, while the 45 to 54 group reported 16.0%. Similarly, the 23 to 34-year-old age group had a moderate risk rate of 15.8%.

Those aged 65 and older reported a slightly lower figure of 12.9%. The lowest rate of moderate risk drinking was found in the 18 to 22 age group, where only 13.2 % fell into this category.

High-risk drinking peaked among individuals aged 55 to 64. In this group, 17.4% reported drinking at increasingly harmful levels.

The next highest group was 45 to 54 years, where 16.6% were in the high-risk category. Adults aged 65 years and older followed with 15.4%, and the 35 to 44 group was close behind at 15.1%.

Among individuals aged 23 to 34 years, 14.2% were considered high-risk drinkers. The lowest rate again appeared among the 18 to 22 group, where only 8.4% consumed alcohol at high levels.

In summary, alcohol consumption risks tend to be lowest among the youngest adults. Middle-aged groups between 35 and 64 years show higher rates of moderate and high-risk drinking, indicating more regular or heavier alcohol use during this stage of life.

Costs and Consequences of Heavy Alcohol Use

Data from the National Library of Medicine gives insights into the direct and indirect costs of alcoholism in Nova Scotia compared to all of Canada.

A detailed breakdown of both revenues and costs reveals that alcohol imposes a net financial burden on the province, mirroring a similar pattern at the national level.

In 2015, the net income in Nova Scotia from liquor authorities amounted to 228 million dollars. This represents just over half of the 434.5 million dollars generated on average by other provinces.

When combined with federal excise tax revenue of 41.9 million dollars and sales tax and other revenue totaling 102.9 million dollars, Nova Scotia’s total net alcohol-related revenue reached 372.7 million dollars.

In contrast, the national average for total net revenue was 848 million dollars. This means Nova Scotia generated less than half the national average for alcohol-related revenues.

On the cost side, healthcare spending related to alcohol in Nova Scotia was estimated at 144.8 million dollars, while the national average was at 333 million.

This included expenses associated with hospital admissions, emergency care, chronic disease treatment, and mental health services linked to alcohol use.

Alcohol-related losses in economic productivity, due to things like absenteeism, reduced work performance, and long-term disability, also cost Nova Scotia another 168.1 million dollars.

Nationally, this cost averaged 514.8 million dollars, meaning Nova Scotia only incurred roughly one-third of the average burden. However, this can be quite significant when adjusted for its smaller population.

Alcohol also placed a notable strain on Nova Scotia’s criminal justice system. The province spent 89 million dollars responding to alcohol-related crime through policing, court proceedings, and correctional services.

Meanwhile, the national average was at 135.3 million dollars. Examples of social harms often associated with alcohol misuse include impaired driving, assault, and property crimes.

In addition to health and justice spending, Nova Scotia incurred 24.8 million dollars in other direct costs. These may include emergency services, administrative overhead, and damage to infrastructure.

The national average in this category was 53.4 million dollars, placing Nova Scotia slightly below half of the average national cost.

When all categories are combined, Nova Scotia’s total net costs from alcohol reached 426.7 million dollars, which is significantly more than the 372.7 million dollars in total revenue generated.

As a result, the province faced a net deficit of 54 million dollars in relation to alcohol use.

Nationally, the pattern is similar but more severe. The total net cost of alcohol use in Canada was 1.0429 billion dollars, while total revenue was 848 million dollars, leaving a national net deficit of 188.5 million dollars.

In both Nova Scotia and across Canada, the costs of alcohol-related harm, across healthcare, economic productivity, and criminal justice, consistently exceed the revenue generated through legal sales and taxation.

Interventions and Solutions to Alcohol-Related Problems in Halifax

Nova Scotia offers several targeted programs and services that address alcohol-related harm by supporting both individuals living with addiction and their families.

The Affected Others program is designed specifically for family members and loved ones of people currently dealing with addiction, including alcohol use.

This program creates a safe and confidential environment for participants to meet in small groups and learn about the science of addiction.

It also covers topics such as how to set and maintain healthy personal boundaries, how to provide support without enabling harmful behavior, and how to prevent burnout.

For individuals seeking direct treatment, the Mental Health and Addictions Provincial Intake acts as the official entry point for all publicly funded mental health and addiction services in the province.

Anyone can call the centralized intake line or submit an online form to begin the process. Intake workers conduct assessments to determine what type of care is most appropriate and make referrals accordingly.

Another important initiative is the Nova Scotia Brotherhood Initiative, which offers culturally responsive health care for black men across the Halifax Regional Municipality.

A team of professionals, including doctors, social workers, psychologists, and psychiatrists, is connected to the patient to provide individual support.

Beyond this, it also provides peer support through community-based discussions like Safe Space Talks and Barbershop Talks, and offers mental health education focused on emotional intelligence, stress management, and healthy communication.

For individuals experiencing mild to moderate challenges or looking for immediate support, the Access Wellness program offers free single-session counseling for those aged 18 and older.

These sessions are short-term and solution-focused but can also serve as a bridge to longer-term care. Counselors are able to provide guidance and, if needed, refer clients to the provincial intake system for further support.

Together, these services represent a broad but coordinated approach to tackling alcohol-related harm in Nova Scotia by meeting people where they are and addressing a variety of needs across individual, family, and community levels.

The Future of Alcoholism in Halifax

If current patterns continue, alcohol-related challenges in Nova Scotia are likely to grow in both cost and complexity.

Direct costs related to alcohol use, including health care and law enforcement, have already reached over $242 million.

Greater increases could be expected when considering other factors like inflation, population aging, and more recent pressures on health systems.

As Nova Scotia’s workforce continues to age, the economic impact of alcohol-related health conditions could intensify, with more people requiring extended care or exiting the workforce prematurely.

Risk-level data from across Canada also suggests a possible rise in moderate to high-risk drinking among adults aged 35 to 64.

More people in mid-life ages may face long-term alcohol-related illnesses, further increasing demand for acute care, mental health services, and addiction treatment.

Without stronger interventions, the proportion of deaths linked to alcohol could also continue rising.

These trends point to a need for proactive policy changes, improved access to treatment, and sustained investment in community-based support to prevent further strain on public systems.

References

- Nova Scotia Department of Health Promotion and Protection. (2008). Culture of alcohol use in Nova Scotia: An exploratory study. https://novascotia.ca/dhw/addictions/documents/Culture-of-Alcohol-Use-in-Nova-Scotia-Report-2008.pdf

- Government of Canada. (n.d.). Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CTADS). Public Health Infobase. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/alcohol/ctads/

- Halifax Regional Municipality. (2021, June 29). Regional Council Report 1115. https://cdn.halifax.ca/sites/default/files/documents/city-hall/regional-council/210629rc1115.pdf

- Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness. (2011). Alcohol indicators: Measuring our progress on reducing alcohol-related harms in Nova Scotia. https://novascotia.ca/dhw/publications/alcohol-indicators-report-2011.pdf

- Statistics Canada. (2024, October 2). Risk levels based on the new Canadian guidance on alcohol and health, by age group and gender. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/241002/t001a-eng.htm

- Canadian Public Health Association. (2022, June). Alcohol consumption in Canada. https://www.cpha.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/policy/positionstatements/2022-06-alcohol-consumption-in-canada-e.pdf

- Nova Scotia Health. (n.d.-a). Affected Others. https://mha.nshealth.ca/en/services/affected-others

- Nova Scotia Health. (n.d.-b). Mental Health and Addictions Provincial Intake. https://mha.nshealth.ca/en/services/mental-health-and-addictions-provincial-intake

- Nova Scotia Health. (n.d.-c). Nova Scotia Brotherhood Initiative. https://mha.nshealth.ca/en/services/nova-scotia-brotherhood-initiative

- Nova Scotia Health. (n.d.-d). Access Wellness. https://mha.nshealth.ca/en/services/access-wellness

- Statista. (2024). Number of deaths attributed to alcohol use in Canada from 2013 to 2019. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1470018/deaths-attributed-to-alcohol-use-canada/

- Canadian Public Health Association. (2022, June). Alcohol consumption in Canada: Reducing the toll through a public health approach [Position statement]. https://www.cpha.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/policy/positionstatements/2022-06-alcohol-consumption-in-canada-e.pdf